Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl performance was billed as entertainment. But for us in the African diaspora paying attention, it rang out as an indictment. I am a Jamaican-born woman with predominantly African roots. The trans-Atlantic slave trade resulted in me also having a smattering of Taíno and European ancestry, and American Imperialism now has me living in the United States. Though I was not born on this landmass, my history is inseparable from the rise of American power.

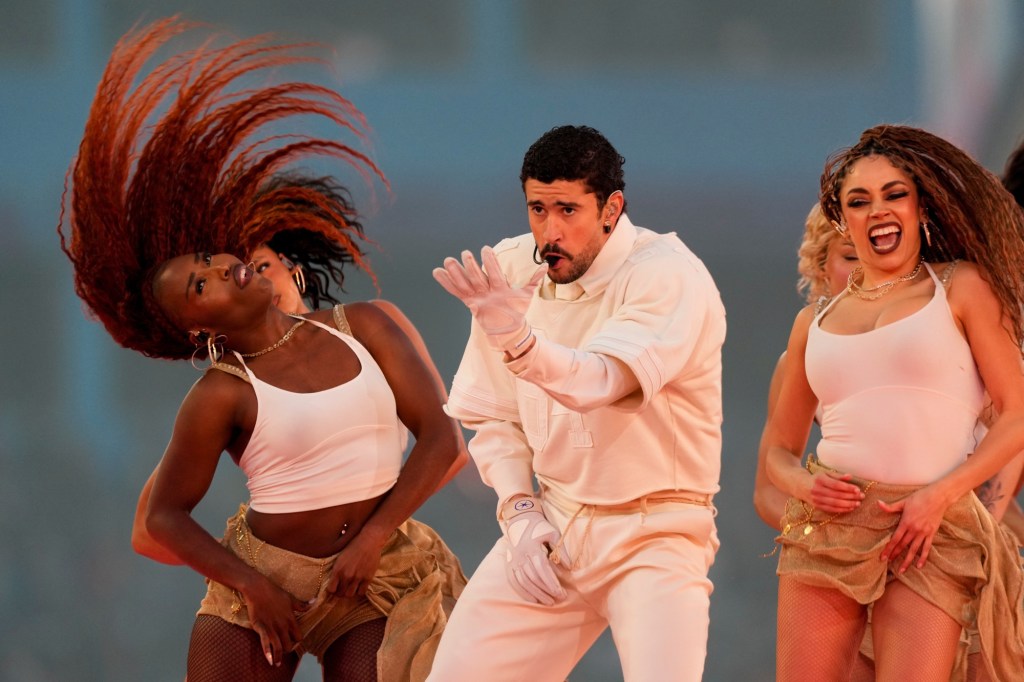

Under the gaze of a stadium drenched in U.S. patriotism, the same arena in which Colin Kaepernick refused to stand for the anthem of a nation practiced in discarding bodies like his, Bad Bunny chose to wave not the official darker-blue Puerto Rican flag tied to U.S. imperial redesign, but the earlier light-blue version- a visual refusal of total submission to empire’s story about itself.

The launderers who weave American mythology will have us believe that this country is uniquely righteous, even as political practice on both sides of the aisle affirms that only a narrow slice of people count as “real Americans.” That fiction does not merely subdue Black Americans; it works overtime to erase Caribbean people, continental Africans, Afro-Latinos, and Black migrants whose labor and lives have fed this project without us ever being welcomed fully into it.

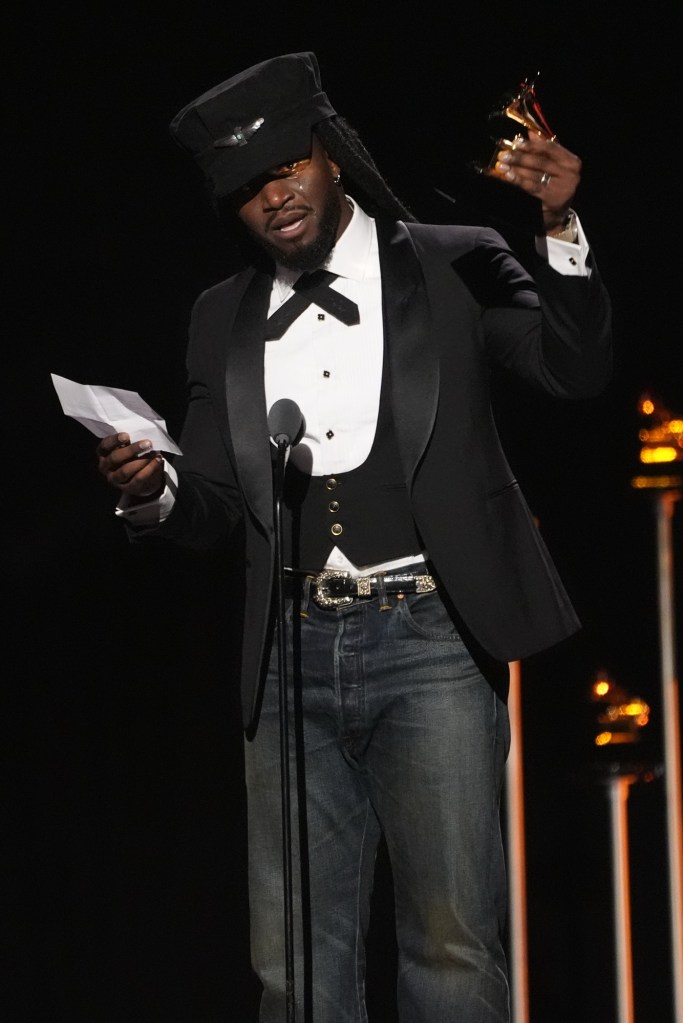

A week before Bad Bunny walked onto the Super Bowl stage, the Grammy Awards brought this American fracture into full view. When Nigerian-American country artist Shaboozey accepted his award for Best Country Duo and declared that “immigrants built this country,” the reaction split along exactly the lines this essay traces: Black Americans angry at erasure, Black immigrants insisting on their place, everyone trapped inside the same small argument. The empire kept humming along in the background. That night posed the question- who gets to claim America?- and a week later, Bad Bunny stepped onto the biggest stage in the country holding a different kind of answer in his hands.

Foundational Black Americans’ anger came from a real wound about erasure. But it also revealed something else to me: a belief that being seen as the ones who “built America” is a prize worth fighting for. The backlash to Shaboozey was full of people insisting, “We built this country,” as a counterclaim, as if America were our proud project instead of something built on top of us.

When the white supremacist, exceptionalist “we” boasts about who built this country, it is never talking about us. It is not talking about enslaved Africans whose labor laid the foundations of U.S. wealth and infrastructure; West Indian migrants who dug the Panama Canal; Jamaican farm workers imported under “temporary” visas and sent home with broken bodies instead of rights; or Caribbean and African immigrants who clean hotel rooms, pick crops, and staff the care economy while being branded perpetual foreigners.

But America was not our idea. We were kidnapped, conscripted, imported, indebted, and deceived into laboring for a capitalist machine that was never intended for our liberty. We owe this system nothing, especially not pride in being named its master builders. Rejecting the scam of American exceptionalism and national pride is simply correcting a misattribution.

This “we built America” rhetoric covers over an ongoing material arrangement in which Black labor, Black land, and Black life are extracted across borders to sustain U.S. power without a corresponding obligation ever being acknowledged. Against that denial, an honest reckoning with the “immigrants built this country” debate- and with Bad Bunny’s moment- pushes me toward a different conclusion: the United States owes reparations to the entire African diaspora, not only within its formal borders but across the imperial circuits it built.

For Black Americans descended from slavery on U.S. soil, the reparations case is already overwhelming. Chattel slavery was not a side hustle that a few bad apples engaged in; it was the central engine of national growth. Enslaved Africans and their descendants cleared land, built roads and ports, and grew the cotton, sugar, rice, and tobacco that financed banks, universities, railroads, and the federal government itself. After emancipation, the state did not simply move on. Convict leasing, Jim Crow, redlining, and mass incarceration retooled racial control, stripping Black communities of land, wages, and political power while maintaining the flow of value whiteward.

Colony of a Colony

But the United States of America owes reparations to every diasporic African. The Caribbean was an incubator for the plantation system that structured the U.S. South. Barbados became a laboratory for sugar-based racial slavery, where white planters amassed fortunes on the backs of enslaved Africans and refined the legal and economic blueprints for large-scale plantation rule. When land ran out, Barbadian elites carried their capital, enslaved laborers, and legal codes to the Carolina coast. Early South Carolina was, quite literally, a colony of a colony- governed and financed by men whose wealth had already been wrung from enslaved Caribbean Black life.

Merchants in New England and the mid-Atlantic grew rich provisioning Caribbean plantations and investing in them, then reinvested those profits in U.S. infrastructure and industry. Caribbean enslavement underwrote U.S. development in two directions: through transplanted planters and through financial circuits that quietly turned sugar and human bondage into northern brick, track, and endowment. Descendants of those enslaved in the Caribbean, therefore, have a direct claim on U.S. institutions built with that blood money.

The Canal and the Bananas

The story continues with West Indian canal and plantation workers and the advance of the American Empire. Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, tens of thousands of migrants from Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad, and other islands traveled to Panama to work on the canal and related projects. Black West Indians formed the bulk of the workforce at key moments, doing the dirtiest and most dangerous jobs in a rigidly segregated wage system that paid them less, housed them worse, and barred them from benefits reserved for white “Gold Roll” employees.

Thousands died from disease, accidents, and overwork as the United States blasted and dredged its way to a waterway that transformed global shipping and cemented U.S. geopolitical dominance. Across the canal zone and Central America, U.S. banana and railroad companies relied on West Indian labor to build agro-export economies designed for U.S. markets. Caribbean migrants lost life and limb chasing wages that rarely matched what recruiters promised them. The canal and plantations, however, delivered to U.S. capital exactly what it desired. Reparations here mean direct recognition and compensation for the descendants of those workers, including pensions for surviving families, funded by the states and corporations that profited, and by U.S. entities that continue to benefit from canal traffic and historical banana empires.

If the Grammys posed the question- whose labor counts when we say “built this country”?- Bad Bunny’s halftime performance widened the frame. His flag, his body, his language, and his island’s history insist that “America” was built not only by people inside its borders, but by those it colonized, imported, indebted, experimented on, and then erased from the story.

Rightless and Deportable

The same United States that treats Puerto Rico as a domestic labor reserve has spent decades cycling Caribbean workers through “temporary” visa schemes: welcome enough to cut cane and pick fruit, and die of Covid due to unsanitary conditions at labor camps, but never welcome enough to belong. Under programs that evolved into today’s H-2A visa, the U.S. systematically recruits Caribbean labor- especially from Jamaica- for seasonal agricultural work. These workers are tied to specific employers, housed in substandard conditions, frequently underpaid or cheated, and almost never offered a viable path to permanent status.

They keep the sugar, fruit, and vegetable economies running while remaining rightless and deportable. This, too, is racialized extraction: using Black Caribbean bodies as a pressure valve for U.S. labor markets while denying them social, political, and economic membership. Meaningful reparations would require compensation for present and former guestworkers and their descendants, regularization for those here now, and labor law reforms that prevent future exploitation.

Before Black Wall Street, Thomazeau

Haiti carries an especially brutal U.S. IOU. After the Haitian Revolution, France forced the new Black republic to pay an indemnity for the loss of enslaved labor and land, plunging Haiti into a century of debt- a system the United States supported, hoping it would contain Black freedom. In the twentieth century, the U.S. occupation seized Haiti’s customs and treasury, imposed forced labor, and deepened extraction by foreign banks.

Before they dropped bombs on Black Wall Street, they dropped them on Thomazeau: in 1919, U.S. planes bombed villages in Haiti’s Central Plateau, strafing Black civilians in one of the first aerial attacks in the Americas. Later, Washington backed the Duvalier dictatorship while Papa Doc and Baby Doc looted the country, murdered tens of thousands, and ran up debts ordinary Haitians are still paying today. Reparations here require debt cancellation, Haitian-controlled reconstruction, and acknowledgment that U.S. policy helped turn the world’s first Black republic into a laboratory of underdevelopment.

Cuba is a clear, enduring example of what it means to be strangled for refusing U.S. terms. For more than six decades, Washington’s embargo has tried not just to stop U.S. trade but to cut Cuba off from the global economy- blocking access to finance, food, fuel, and medical supplies, deliberately seeking, to borrow Kissinger’s phrase about Chile, to “make the economy scream” and force political collapse. Now, a new executive order threatens tariffs on any country that ships oil to the island, and Mexico- under direct pressure- has paused crude deliveries, leaving Cuba to log its first oil-import-free month in a decade and pushing a fuel-starved society into yet another manufactured crisis. When the U.S. announces there will be “no more oil or money for Cuba: zero,” it is doing in public what it has long done in policy: treating a Black and brown nation as something to be starved into obedience, and its people as acceptable collateral.

Testing Grounds

From Bad Bunny’s homeland, in 1931, Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads of the Rockefeller Institute wrote a letter boasting that he had deliberately infected Puerto Rican patients with cancer and fantasizing about exterminating the island’s population. Though later investigations minimized his words, he went on to run U.S. Army chemical weapons labs that tested gas on Black and Puerto Rican soldiers.

The same empire that now markets Puerto Rico as a tax haven and tourist fantasy used its land and people as testing grounds for bombs, debt, austerity, and medical racism. On the island of Vieques, U.S. military expropriations displaced Black and Caribbean communities and left behind environmental and health disasters. Because plantation life fused workplace and home, workers lost job and shelter in a single stroke and were dumped into “resettlement” strips in the middle of the island, with the main sugar mill shuttered and no new economy to replace it.

When the United States speaks of “security” in the Caribbean- through the war on drugs, border enforcement, or military patrols- it deploys the same imperial logic in a new uniform: Black lives rendered as threats to be managed rather than neighbors to be protected. In October 2025, a U.S. military helicopter strike on a boat off Venezuela killed two Trinidadian citizens, Chad Joseph and Rishi Samaroo. Their families say they were returning from fishing and farm work; Trinidad’s government reports no evidence linking them to drugs or weapons, and the U.S. has not attempted to furnish any.

Here again, Caribbean lives are rendered collateral at the edge of empire. Any serious reparations horizon must count these deaths as part of the bill.

On the Mainland(s)

This same logic stretches across the Atlantic. In Congo, the United States helped sustain the Mobutu dictatorship for decades, providing aid and weapons as he looted the state and crushed opposition. Structural adjustment followed, hollowing out public institutions while debt service flowed whiteward. Today, as Washington competes for critical minerals, U.S. companies operate within supply chains tied to militarized mining, displacement, genocide, and child labor.

Inside the United States, these imperial debts reappear as engineered division. Hiring pipelines, university recruitment, and corporate diversity strategies are designed to select Blackness without the political freight of U.S. slavery. In that context, it makes sense that Black immigrants reach for “good immigrant” narratives to survive, and that some Foundational Black Americans harden lineage-based boundaries to protect a debt they paid for with centuries of history. These are not opposing moral failures; they are survival strategies produced by the same machine.

The tragedy is that this zero-sum fight serves the laundered American innocence perfectly. Every moment spent arguing over who “built” the country is a moment not spent demanding repayment from the systems that extracted from every single one of us.

To say the United States owes reparations to the entire African diaspora is not to erase specificity. It is to insist that the map of debt match the map of extraction. Different histories generate different claims, but they converge on the same conclusion: the wealth of the United States rests on coerced Black labor across borders and centuries. Black Americans descended from U.S. slavery are owed for centuries of direct bondage and its ongoing afterlives. Caribbean descendants of enslaved people are owed for the ways their ancestors’ labor and their islands’ wealth were funneled into U.S. development. West Indian canal and plantation workers’ families are owed for the bodies sacrificed to build U.S. empire. Caribbean guestworkers and their children are owed for generations spent as disposable labor. Haitians, Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, and others are owed for the occupation, expropriation, experimentation, and militarization that fed U.S. power while hollowing out their own states. Cubans are owed for six decades of deliberate economic strangulation designed to crush a sovereign Black and brown nation for refusing U.S. terms. Africans in places like Congo are owed for decades of U.S.-backed dictatorship, debt, and mineral extraction that tied their futures to someone else’s battery and defense supply chains.

The sequence of the past two weeks felt almost choreographed. At the Grammys, a Black child of immigrants said “immigrants built this country” and ignited a fight over authorship. At the Super Bowl, a mestizo Puerto Rican artist entered the heart of American spectacle holding a flag that said, without a word, that the project was never just theirs to claim- and never ours to be proud of building.

The United States is not exceptional because it is innocent. It is exceptional because of the scale of what it has taken. A diaspora-wide reparations claim is impossible to deny. Reparations are not a gift from a benevolent power. They are the minimum down payment on a debt that has been accruing since long before the first kickoff.

Leave a comment